2022-01-04 Articles

When a Piece of Cheese Can Help Avoid Many Mistakes

January 4, 2022

We’ve all heard the expression “to err is human”. Lawyers, whether they are beginners or experienced, or whether they practice solo or in a large firm, are not immune to this reality.

In this article, we will present the Swiss cheese model (Reason model) which, on the one hand, allows us to understand why an error occurred so we can learn from it and, on the other hand, can be used to perform a risk management analysis. We will also discuss the application of this model to the prevention of malpractice proceedings.

1. Birth of the Swiss Cheese Model

The late 1980s were marked by several disasters: the Chernobyl and Challenger shuttle explosions (1986), the fire at King’s Cross subway station in London (1987), the Exxon Valdez oil spill (1987), the Herald of Free Enterprise maritime accident (1987) and the Piper Alpha explosion (1988).

Since then, the scientific community has been interested in the etiology of accidents, that is, the study of their causes. The work of University of Manchester professor and psychologist, James Reason, is part of this field of study. In 1990, he proposed the Swiss cheese model to not only understand the causes of certain serious accidents, but also to try to prevent them.

Since then, the application of the model has been extended to other types of accidents, such as medical errors, plane crashes and financial fraud. As we will see below, the model is also relevant to understanding and preventing professional errors in the practice of law.

2. What is the Swiss Cheese Model?

2.1. A Systemic Approach

First of all, the Swiss cheese model takes a systemic approach to the occurrence of an error. Of course, human beings are fallible and mistakes are to be expected. It can be tempting and emotionally satisfying to blame an individual for the occurrence of an error. However, errors rarely have a single cause, which is why the systemic approach sees them as consequences whose origins lie not so much in the fallibility of human beings, but in upstream systemic factors. In other words, as regards the occurrence or prevention of errors, the model recognizes both the role of front-line individuals and the role of the organizational environment and the managers who shape it.[1]

2.2. Explanation of the Model

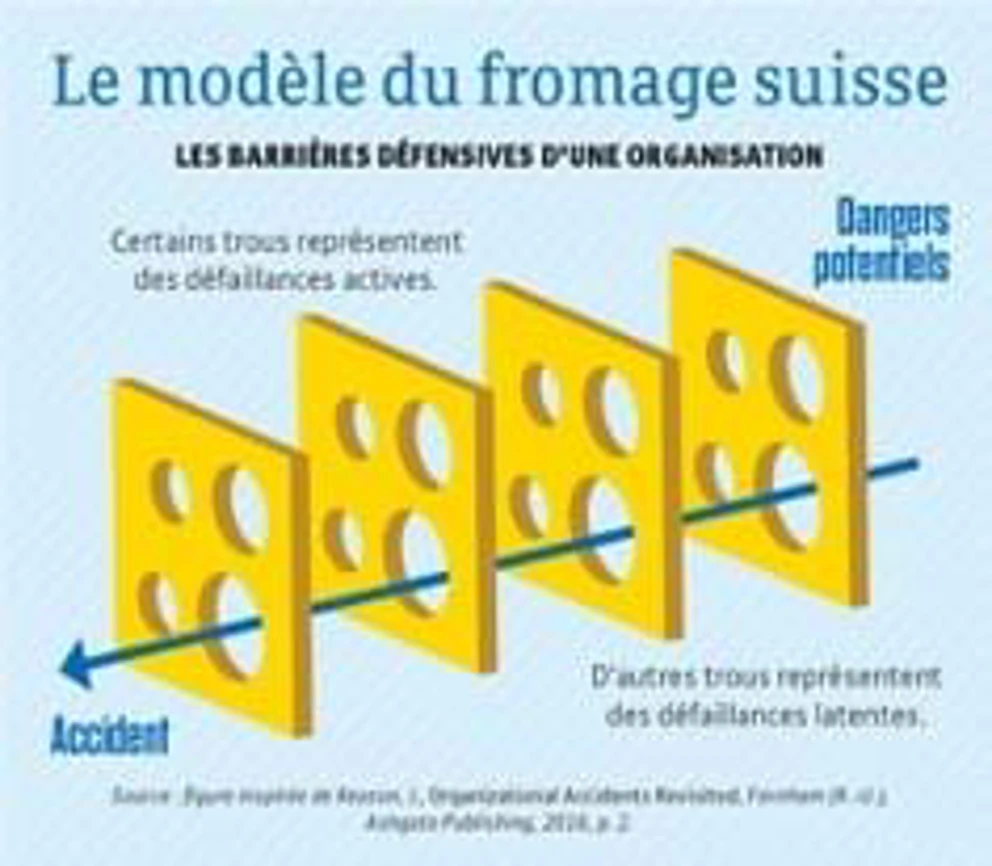

To illustrate his approach, Reason proposed a representation inspired by the shape and appearance of Swiss cheese, hence the name of the model.

According to Reason, a system has different defences, barriers or safeguards whose function is to prevent the occurrence of errors. In the model, these defences, barriers and safeguards are represented by the cheese slices. In concrete terms, they include a firm or company’s senior management, human resources department, lawyers, assistants, procedures and policies.

In an ideal world, the cheese would have no holes. However, in reality, the cheese is cut into several thin slices, each with several holes in different places. The holes represent defence weaknesses or failures. They are dynamic, meaning that their size and location change based on decision making, audits, maintenance, human errors, etc.

Reason identifies two types of weaknesses or failures: active failures and latent conditions.

Active failures are dangerous acts committed by persons in direct contact with the patient or client or the system. Applied to the field of law, they can involve lawyers and their assistants. These dangerous acts take many forms: slip-ups, missed deadlines, errors and failures to follow procedures. Active failures have a direct impact on the occurrence of the error.

As for latent conditions, they are the result of decisions made by designers, developers, procedure writers and senior managers. Latent conditions can remain dormant for a period of time until an active failure reveals them.

A decision may not necessarily be intrinsically wrong. As Cinthia Duclos, a law professor at Université Laval law and co-director of the financial services research group, points out, a “bad decision” is one [translation] “where the organization puts productivity and profitability ahead of employee safety and client protection”.[1]

Latent conditions have two types of negative effects: they can result in conditions that cause errors in the local workplace and they can create holes or lasting weaknesses in defences.[2]

In general, errors occur due to a combination of these two types of weaknesses or failures. In fact, a mistake can go unnoticed or have no serious consequences if it only crosses one slice of cheese. On the other hand, it can lead to a catastrophe if the holes in the various cheese slices overlap and all safety measures fail simultaneously. The blue arrow represents a succession of errors of all types creating an accident trajectory.

3. Application of the Swiss Cheese Model to the Professional Liability of Lawyers

A lawyer in private practice fails to file proceedings, thereby leading to the loss of the client’s rights. At first sight, the lawyer seems to be the only one responsible for that loss.

However, the use of the Swiss cheese model highlights the fact that the lawyer’s assistant also failed to inform the lawyer of the deadline. This is a failure (hole) in a second defence barrier (cheese slice).

Both the lawyer and the assistant blame an overload of work for their respective omission. The lawyer mentions that he has too many cases. As for the assistant, she is assigned to help four lawyers.

Further analysis reveals a series of upstream decisions. More specifically, several budget cuts have restricted the resources allocated to hiring new employees and have also reduced the training offered. These decisions, therefore, also constitute failures (holes) in a third defence barrier (cheese slice).

The Swiss cheese model allows us to see that the lawyer’s failure to initiate proceedings within the required time limit was only one error among others and that it was the logical consequence of upstream decisions.

The Swiss cheese model can also influence the corrective measures proposed to limit the occurrence of an error. A first-level analysis that looks at the direct cause of the error will result in corrective actions limited to the lawyer, such as a warning. However, a deeper analysis will involve actions at other levels.

4. Preventive Measures

One question remains: How can you implement the Swiss cheese model in your practice?

Here are our suggestions:

-

Identify and define risks

This involves identifying the risks to which your firm or company is exposed and which could influence the expected results. The risks you need to think about may be related to the lawyers and employees of your firm or of the company in which you work. They may also be related to some of the firm’s clients or the company’s suppliers. In addition, it is important to extend your analysis to senior management decisions and to the policies and procedures put in place.

-

Identify risk responses

Establish strategies in light of your budget, time frame and available expertise in order to manage risks and reduce the likelihood of them occurring.

For example, continuing education is one of the strategies that come up frequently with regard to risk management. This training should cover not only the substantive law, but also best professional practices and the prevention of malpractice proceedings.

Another example is to have internal processes (e.g.: conflict of interest searches) or checklists (e.g.: opening files). These processes or lists can allow you to identify a problem that would otherwise go unnoticed given the hectic pace of the practice of law. They also limit the risk of forgetting something. That said, when it comes to processes, it is important to ensure that they can be realistically implemented. Moreover, given that risks evolve, it is also important to regularly review your processes and lists in order to ensure their relevance.

-

Develop a reporting culture within your organization

This implies that each stakeholder feels involved in risk management and can report weaknesses or failures they notice within the organization, with the objective of continuous improvement.

In closing, it is important to remember that the Swiss cheese model can not only allow you to learn from your mistakes, but also to effectively manage risks and reduce those related to professional liability. In this sense, it allows organizations to be more resilient and reduces the perception of always having to “put out fires”.

References:

Cinthia Duclos, “Le modèle du fromage suisse : Quand les failles s’additionnent”, Gestion HEC Montréal, November 24, 2021, online: https://www.revuegestion.ca/le-modele-du-fromage-suisse-quand-les-failles-sadditionnent.

Douglas A. Wiegmann, Laura J. Wood, Tara N. Cohen and Scott A. Shappell, “Understanding the “Swiss Cheese Model” and Its Application to Patient Safety”, (2021) Journal of Patient Safety, online:

James Reason, “Human error: models and management”, (2000) 320:7237 Bmj 768, p. 769, online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1117770/.

Justin Larouzée, Franck Guarnieri and Denis Besnard, “Le modèle de l’erreur humaine de James Reason”, [Research Report] CRC_WP_2014_24, MINES ParisTech. 2014, 44 p. ffhal-01102402f.

Mikael Krogerus and Roman Tschäppeler, Le livre des décisions, Paris, Éditions Alisio, 2018, 176 p.